4Oct2022

Historian and author Rutger Bregman’s basic question to those in attendance at the Nordic Business Forum is this: are people inherently selfish, or are people inherently helpful?

When put to a vote, the majority of the audience (58%) believes that we are inherently selfish, while 42% believe the opposite.

Bregman’s talk aims to show two things: the 58% are wrong; humans are not selfish by nature. But also—as a practical implication—coming to believe and act as if we’re not selfish by nature can actually produce some significantly positive results.

Two Theories of Human Nature

The Veneer Theory—Bregman explains is “the notion that our civilization is just a thin veneer…and below that lies raw human nature…In times of crisis, we show who we really are: Animals, beasts. It’s basically a dog-eat-dog world out there.”

The theory is quite old and finds adherents all the way back to the ancient Greeks, St. Augustine, Thomas Hobbes, and even modern economists. In fact, Hobbes’s theory of civilization and government rests upon the idea that we organized hierarchy and laws in order to keep humanity from descending back into the “war of all against all.”

A New View of Human Nature is one that questions the idea that we’re merely selfish animals run amok. In fact, it posits that humans are basically cooperative and considerate—rather than selfish and careless. It gives us reason to be optimistic and to act differently toward our fellow humans as a result.

And as Bregman explains, this view is not “armchair philosophy”—rooted only in hope, but not in evidence. In fact, scientists from psychology, sociology, economics, biology, and beyond have been finding evidence that points toward this new view of human nature for decades. Bregman invites the audience to consider this evidence—consider changing our worldview based on it, and seeing if we don’t end up with much richer experiences.

The Sociological Basis

One of the key questions related to human nature is what do humans do in times of crisis? The tendency of Planet A thinkers tends to be that people are selfish. In times of scarcity and uncertainty, the thin veneer of civilization drops away.

But Bregman points to over 60 years of research done by the Disaster Research Center in the U.S. Anthropologists and sociologists have done over 500 case studies. The findings, Bregman says, fly in the face of the Veneer Theory.

“What they’ve discovered is that actually, time and time again, disasters tend to bring out the best in people.”

The Psychological Basis

A favorite dynamic duo offered up by proponents of the Veneer Theory is The Bystander Effect and the story of Kitty Genovese. The Bystander effect is a phenomenon where the more people are around to witness something bad happening, the less likely anyone is to intervene. The story of Kitty Genovese is often offered as proof of this effect.

Genovese was a young woman who was killed outside her apartment building in 1964. A man had been stalking her with a knife for an hour, and as he pursued, attacked, and killed her, none of the 37 people present at the time intervened. Numerous psychological experiments have been performed, books written, and documentaries made—all arguing the truth of the Bystander Effect.

But Bregman presents a compelling objection to this kind of thinking: what happens in the lab is not human nature. What happens in the real world—when push comes to shove—that’s what can show us human nature. He presents a short video shot in Amsterdam of 2 men jumping in a canal to save the baby of a woman who left her parking brake off. The men immediately jumped in, smashed the window of the car as it sank, and saved the child. An army of bystanders then helped the men get out of the water safely.

And this case alone is not unique. In fact, Bregman argues, in 90% of cases that researchers found in the real world (using surveillance footage), there was no instance of the Bystander Effect. People tended to help others with little hesitation. Social Psychologist Marie R. Lindegaard has created a huge database and published work in top psychological journals effectively debunking the Bystander Effect.

The Biological Basis

Richard Dawkins’s The Selfish Gene is a legendary book in the field of evolutionary biology. But one of its main arguments seems to say that selfish behavior is built-in to animals in general and humans in particular. And what’s more, it’s reinforced by evolution because the most selfish animals have lived to preserve themselves and pass on the tendency to be selfish.

This is a compelling argument, but Bregman brings up two key counterexamples to that theory:

Blushing – Humans are the only primates that blush. But the primary feature of blushing is that it puts our emotions (and vulnerability) on display for others. It seems like that kind of feature simply would not survive in an evolutionary framework built to weed out anything but selfish traits.

The whites of our eyes Humans are the only primates with white sclerae, and they are notably larger than other primates. All other primates have dark or black sclerae—which makes it difficult to track the gaze of other primates—a useful function in the wild. Humans, however, have large, bright wite sclera. They’re perfect for building trust, but not so much for propagating a selfish evolutionary narrative.

Self-Domestication

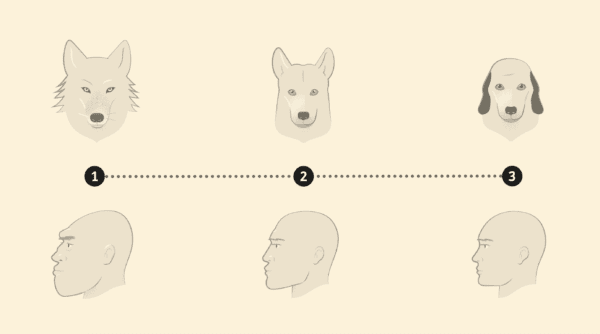

Bregman points to these two features of humans as evidence of something biologists call self-domestication.

Normal domestication happens over a long time frame, and usually involves a checklist of feature changes. Specifically, you see a smaller brain than predecessors. Chief among them is a behavioral one. They become more friendly.

With humans, over time, we’ve gone through this checklist. Our brains are smaller than Neanderthals by quite a bit. Our behavior has tended to become more cooperative. Bregman provides a great illustration of this from an anthropological journal that compares the facial features of dogs during their domestication to those of humans during ours.

It’s quite clear that much like the wolf’s journey to a pet dog, the Neanderthal’s journey to modern homo sapiens is one of looking more and more friendly over time. Bregman jokes that the modern human species we see on the right can be scientifically renamed “homo puppy”.

The Alternative View in Practice

Veneer theory—as Hobbes argued in Leviathan—necessitates hierarchy and rules to keep people from being selfish. But if we find, as Bregman argues, that it’s not true, then we can radically reorient social structures—from companies all the way up to governments.

We see so much dissatisfaction and transience in the workforce, and Bregman believes that it’s due to Veneer Theory thinking in company structures. But it doesn’t have to be this way. We can change our outlook on human nature, and actually see the positive results. And that’s already happening. Bregman provides 2 examples.

Buurtzorg is a Netherlands-based home healthcare company built on a more optimistic view of people.

It’s grown to over 50,000 employees, and become the most successful healthcare company in the Netherlands. The teams are self-directed, rather than a top-down hierarchy with strict rules and regulations. It pays the highest wages paid to employees in its economic sector. But yet, it’s also consistently cited as one of the best healthcare providers. And it is widely known for delivering extremely cost-effective service to the government.

Bastoy Prison is a prison on an island in Norway that looks and feels more like a quaint country vacation island than a prison. Inmates are allowed to sunbathe, freely hang out with guards, and even use chainsaws to cut trees—even if they literally killed someone with a chainsaw to get sent to prison in the first place.

Rather than a focus on vengeance, retribution, and punishment, this model focuses on cultivating the intrinsic cooperative nature of humans. And what’s more? Bregman reports that Bastoy is often cited as one of the best prisons in the world when it comes to the most important metric of prisons: recidivism. Inmates from Bastoy are very unlikely to end up committing crimes once back in society.

This, Bregman argues, is no accident. Just like our view of the world tends to color how things turn out for us, how we treat others tends to become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Bregman closes with a quote from the warden of Bastoy Prison, Tom Eberhardt:

“Treat people like dirt and they’ll be dirt. Treat them like human beings, and they’ll act like human beings.”

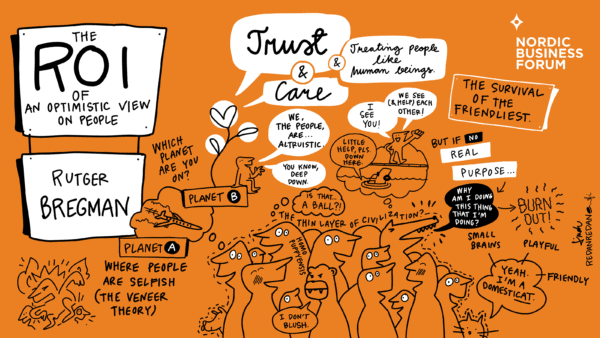

Visual summary of Rutger’s keynote by Linda Saukko-Rauta