3Oct2022

How do we create and lead organizations that thrive in times of uncertainty? According to the world’s number one management thinker and Harvard professor Amy Edmondson, it’s not about erring on the side of caution, it’s not about demanding flawlessly executed excellence of our teams, and it’s certainly not through fear.

Rather, Edmondson explained, it’s establishing psychological safety. What that looks like—and doesn’t look like—and what it takes to build a psychologically safe and resilient organizational culture was at the core of her presentation at Nordic Business Forum 2022.

What Is—and What Isn’t—Psychological Safety

Edmondson’s formal definition of psychological safety hinges on the expectation and belief within a team that it is safe to take interpersonal risks. What does that look like? It’s feeling safe enough to speak up about mistakes and concerns while being unafraid to bring up ideas and questions too. This security comes from a belief that you will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up.

The idea of psychological safety has garnered more attention in recent years thanks in large part to a study at Google, which found that the presence of psychological safety was the top thing that explained performance discrepancies across the company’s various teams.

However, also thanks to that study, a number of misconceptions about psychological safety have arisen, Edmondson said. She clarified that psychological safety is not:

- Being nice

- Job security

- A guarantee all your ideas will be applauded

- An excuse to complain

- Freedom from conflict

- Permission to slack off

There is no trade-off between having high standards and psychological safety. In fact, the “Holy Grail” situation was to sit in a “high-performance zone”, where there was both high psychological safety and high-performance standards.

The Proof Is in the Studies

Edmondson described a couple of studies that showed the impact that psychological safety could have. One was a study of 23 intensive care units in hospitals across North America, which found that in some of the teams the levels of psychological safety were the same no matter what roles people were in. Three years on, these teams showed an 18% improvement in the quality of their work, resulting in less mortality of patients.

“Study after study…have shown a consistently positive relationship between psychological safety and team performance,” Edmondson said.

In a meta-analysis of several studies on psychological safety, it was found that the relationship between psychological safety and performance was most strongly associated with work that was “knowledge-intensive”. In other words, work that required more creativity, complexity, ingenuity, and judgment.

Another study tackles the question of where diversity fits in. This study on 62 innovation teams in the pharmaceutical space showed that diversity alone is not enough to guarantee performance. What was the difference between the teams with diversity that thrived and those that didn’t? You guessed it—psychological safety.

How Leaders Can Create a Psychologically Safe Environment

Talking about psychological safety is one thing, but actually implementing it requires the right approach. According to Edmondson, there are three key ingredients to creating an environment where people feel safe to take interpersonal risks.

1. Frame the work

Make it clear that the work requires people’s voices and input, and that speaking up is encouraged. Edmondson gave an example of Julie Morath, a leader in quality and safety in the health space, who often said that the nature of healthcare meant it was a complex, error-prone system. Things will go wrong, but the crux is: are people speaking up about it? Instead of viewing this as admitting incompetence or snitching, see it as actually trying to save people’s lives.

2. Invite participation

The easiest way to do that is to set an example. Ask good questions – ones that invite thought, that focus on the issue at hand, and give people room to respond. Ask: “What are we missing?” “Who has a different perspective?” “Oh that’s interesting – can you walk us through that?”

A piece of helpful advice Edmondson gave here was to seek “consent, not consensus”. Rather than think you have to get everyone to agree if you invite participation, aim for consent. This means that even if people don’t necessarily agree, they at least can say there is no danger or harm in pursuing the idea.

3. Respond productively

When your team is in a place where they are adding their voices truthfully and without fear, you also need to know how to respond.

Edmondson told the story about how Ford Motor Company’s former President and Chief Executive officer Alan Mulally turned the company culture around for the better. The senior executive team had become accustomed to associating speaking up with losing their jobs, so they would lie. Instead of encouraging this behavior, Mulally asked what wasn’t going well and, importantly, did not punish his team for telling him the truth. Rather, he was both appreciative of the feedback and future-focused, by saying, “Thank you…how can we help?”

It’s here that Edmondson summed up these key ingredients with one word to describe each: humility, curiosity, and empathy.

“I think framing the work happens naturally when you come from…a place of humility. Inviting participation, that comes from a place of curiosity, from reinvigorating the curiosity that you were born with, to use it to learn as much as you can from your teams, from your colleagues.”

“And finally, the productive response…comes from a place of empathy. How would I want you to respond to me if I was about to ask for help, or say something difficult, or bring bad news? I would want you to respond in a thoughtful and productive way, to be interested in what I had to say and not to shoot the messenger.”

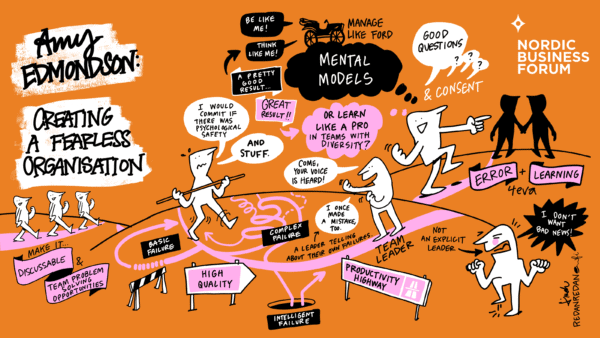

Visual summary of Amy’s keynote by Linda Saukko-Rauta