12Dec2016

With the advertising-industrial complex on a long, slow funeral march, Scott Galloway predicts the future of digital media—and how businesses will have to change in order to survive.

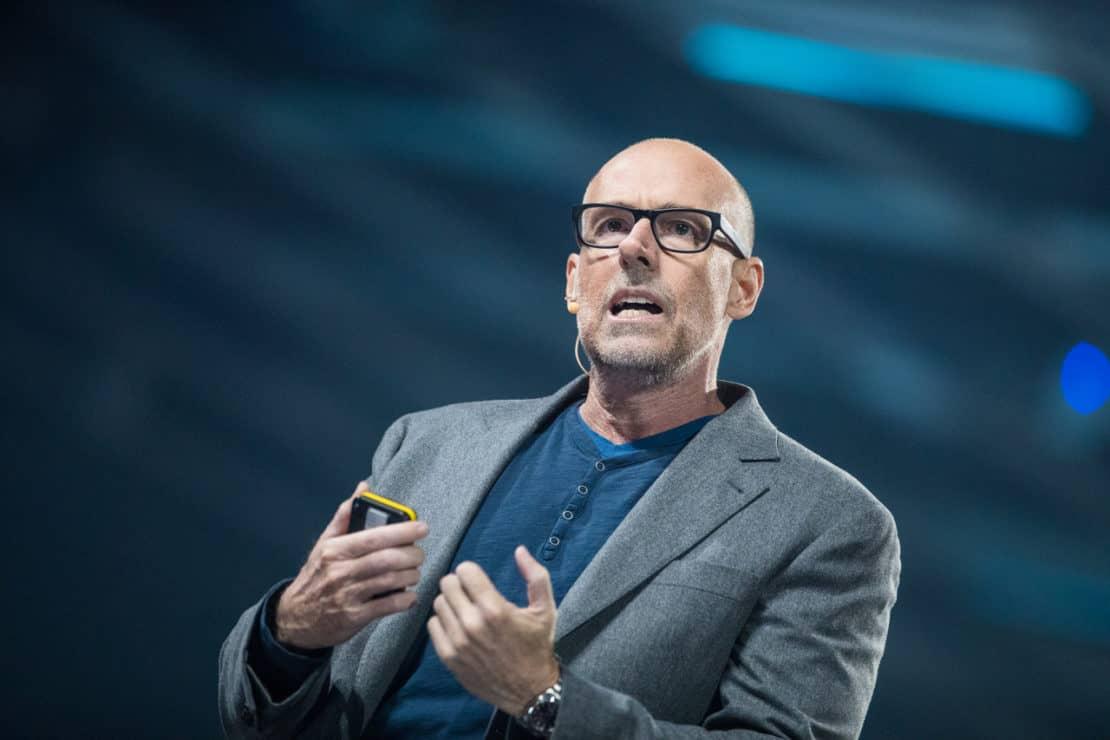

If you ask Scott Galloway what he does for a living, he might tell you he teaches marketing at NYU. Or he might tell you he’s in the business of predicting the future.

Galloway will be the first to admit his predictions aren’t always perfect: In his infamous 2015 talk, “The Four Horsemen,” for instance, he declared Amazon would decline in value if it didn’t open brick-and-mortar stores. “The moment I said this, it went viral. The whole world was ready, jonesing to hate Amazon,” Galloway said. Naturally, the stock price skyrocketed.

Win, lose, or draw, Galloway promised he would hold nothing back at the 2016 Nordic Business Forum: “I have 135 slides and 35 minutes,” he warned, “so fasten your seatbelts.”

The sun has passed midday on the brand

There used to be a simple algorithm for building a brand: You create an average product. You slap a brand code on it—”American and masculine” or “Italian and slim”—and then you beat consumers over the head with print and television advertising. “This is the algorithm of the greatest increase in shareholder value in history since World War II,” Galloway said.

That was then when we didn’t have the time to find the exact right product and instead deferred to the brands who messaged the loudest. Today? Well, it’s a different story.

Imagine you see a trendy hotel on Instagram. You look for it on Facebook and realize that all your young, cool friends have stayed there, liked the page, written a review—and suddenly, you want nothing more than to spend a night there, too. “The path of product discovery has shifted,” Galloway announced. “Your favorite brand is what Amazon or Google are about to tell you that your favorite brand is.”

The advertising sword is dulling

At the crux of Galloway’s argument was this: The fastest growing brands right now don’t advertise anymore. Why would they? Across the United States and Europe, viewership for some of the biggest television brands has declined by as much as a third, replaced instead by over-the-top media—“essentially, media that is anytime, anywhere, and no commercials.”

Leading the change in how we consume our media, Galloway observed, is “the young and wealthy.” They’re the ones cutting the cord, the ones who will pay a premium for ad-free experiences, the ones who decided the old broadcast media bargain—if they give us free content, we’ll endure the advertising—was broken.

Take Business Insider, who makes about two quarters for every reader served an advertisement: “Tell you what, here’s 60 cents. Save me from your shitty advertising!” Galloway joked. “That is where the world is headed.”

Stores are still the most influential factor in the purchase decision

If more and more consumers are tuning out advertising, how are businesses supposed to reach their consumers? Galloway’s answer is simple: the brick-and-mortar store—which, to this day, outranks search, CRM, and social media in its impact on purchasing behavior.

Consider the two biggest producers of the smartphone: Apple and Samsung. Relative to its revenue, Samsung allocates twice as much budget to advertising, while Apple invests in its 480 stores—or, as Galloway put it, in its 480 bright and inviting “temples to the brand.” Of the two companies, he asked, “who do you think is winning?” Exactly.

“The store is the first kiss,” Galloway explained. When you set foot in an Apple store, you enter into a kind of relationship where “you feel good about yourself, and you feel even better about the person you’re being physical with.”

Get into a business that has recurring revenues

After the first kiss, traditional marketing wisdom would have us perpetually reacquire the same customer: Send him coupons. Shower him with more advertising. Mark down products at the end of the season. “It’s exhausting,” Galloway said. His advice to businesses today? Stop dating your customers on and off. Embrace monogamous, long-term relationships—and the beauty of recurring revenue.

Procter & Gamble, for example, has partnered with Amazon’s Dash Button program, devices which can be placed around a consumer’s house. If you run low on detergent, you hit the button on top of your washing machine, automatically adding the same product, from the same brand to your Amazon Prime cart.

It’s cheaper. It’s simpler. It means your customer suddenly has a greater lifetime value, Galloway said, “and you aren’t constantly stopping and starting, trying to resell to the same customer.”

More money on R&D

Galloway pointed out that in the auto industry, four of the top five advertisers have one thing in common: They’re all declining in market share. The most-searched car company? Tesla, who spends next to nothing on advertising.

“Now, innovation in auto is true innovation,” Galloway said—not simply sticking Cindy Crawford in a Cadillac ad. “I get a tune-up wirelessly on my car, and then they send me an email saying, ‘Overnight we tuned up your car.’ Tesla is reallocating all of [its advertising budget] into R&D.”

Even outside the auto industry, Galloway noted, we see the same pattern: Dollar Shave Club outstrips Gillette in search volume, even though the latter owns 82% market share. Last year alone, Estée Lauder and L’Oréal lost 3% market share to nimble, independent beauty brands. The takeaway? Invest in your product, not advertising. “I think that great products do break through,” Galloway said, “that people will find them and share them.”

Digital marketing is a great place to work, as long as you work for Facebook or Google

Somewhere in India, a snake farmer ventures out onto his land to collect thousands of small, commercially worthless snakes. He stuffs them in a chest, shuts the lid, and turns the key in his padlock. When he opens the chest a month later, there are now two large snakes he can turn for a profit. “That is the world of digital marketing,” Galloway said. “It’s full of anxiety, humidity, and death.”

In his analogy, the snakes left in the chest are Facebook and Google: For every dollar reallocated out of traditional advertising budgets, these two companies take a whopping 90 cents, while everyone else is left squabbling over a dime. It’s no wonder, Galloway said, when Google is “the most trusted person in the history the world,” and when Facebook is allowing us to connect and “love at scale.” If we want to share great ideas, these are the places we turn to.

Eventually, Galloway theorized, the public will grow tired of privacy violations and call for the break-up of Facebook and Google. Until then, the “beach party will get bigger and bigger, and the DJs more and more famous.”

“I’m not here with a message of hope.”

Following his breakneck, 100-plus-slide presentation, Galloway answered just one question from the audience: If traditional media is dying, digital media is a death trap, and small, niche brands are thriving, what hope is there for big companies? Not much, he said, but two options:

First, take a hard look at your business model and ask yourself, “Am I advertising and building my brand on channels that are on a structural decline? Am I distributing through retail channels that are in structural decline?” Put another way: “Have I unwittingly entered into a suicide path?”

Most importantly, Galloway said, take a cue from Yoda and “forget what you know.” “The new consumer has new technology and a new way of approaching consumer discovery,” he explained, “so you have to experiment and be willing to fail.”

This is not, as Galloway admits, a message of hope—but it is a message to embrace failure, to walk bravely into the unknown and fail over and over again. The alternative, he said, is failure by default.

This article is a part of the Executive Summary of Nordic Business Forum 2016. Get your digital copy of the summary from the link below.