7Oct2016

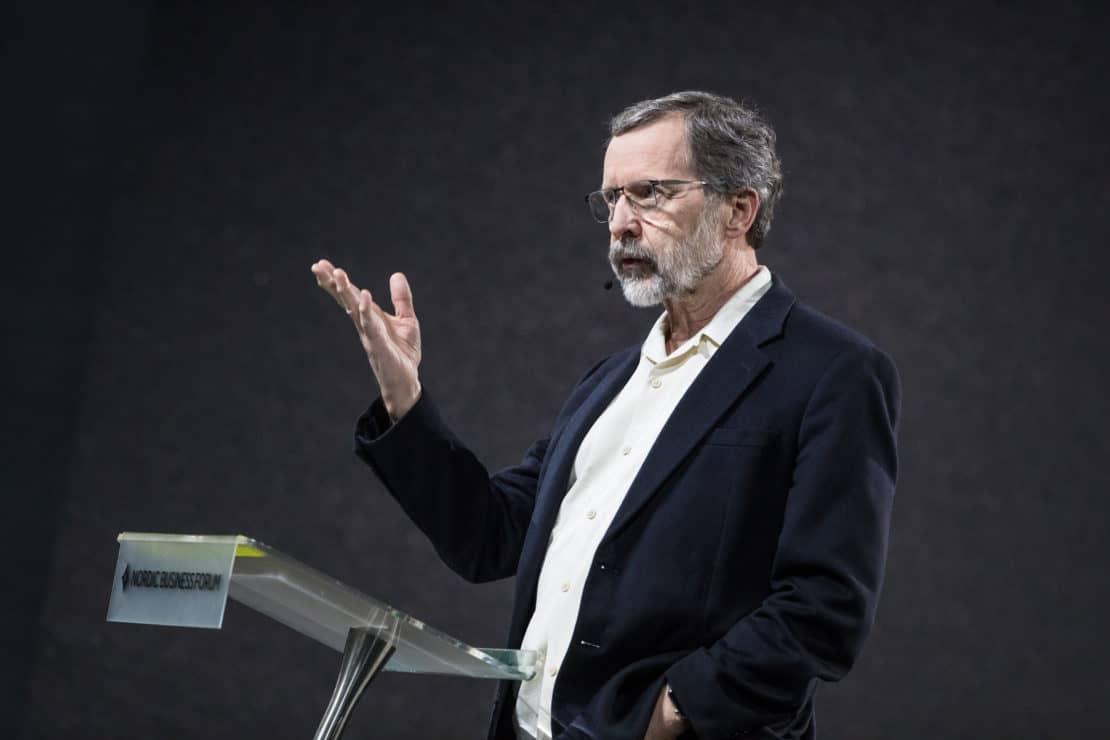

How does one maintain and foster a creative culture? And what are the forces that block creativity? Pixar Animation Studios head Ed Catmull sought to answer both questions during his talk at the Nordic Business Forum.

Much of Catmull’s talk centered around a single fact: the team behind Pixar’s run of animated blockbusters such as Toy Story, Finding Nemo, and Zootropolis, is largely the same group of creators that worked at the studio when it was not producing successful films.

“When we arrived, the studio was considered to be a failure and not producing films,” Catmull said. “Now they are very successful and creative but they are largely the same people who were there when they were failing,” he said. “The talent was there,” noted Catmull. “We just had to remove the barriers and allow their creativity to flower.”

Catmull said this illustrated his central message to attendees: “Everybody has the potential to be creative. It is our choices that block or enable that creativity.”

In order to remove the blocks that were restraining Pixar’s creative team, Catmull said that management embraced a few core concepts. One was that “if you give a good idea to a bad team, they will screw it up.” In contrast, a good team could only take a bad idea and either scrap it or propel it in new and interesting directions.

This challenged the convention of generating ideas first and then finding the people to carry them out. Rather, at Pixar, they sought to maintain a good team and then let the ideas follow.

They also established a set of four operational principles to encourage the creative process. The first was one of peers talking to peers, rather than, say, boss to filmmaker.

“We remove the power structure from the room,” said Catmull. “The director is the one who is allowed to choose what works and what doesn’t work,” he said. “By not allowing anybody else in the room to override the director, it frees him or her to listen.”

Pixar’s second principle was to support an honest exchange within meetings. Directors don’t have to take the suggestions but they do acknowledge there is a problem if it is raised. The firm’s third principle was one of shared ownership of the group’s collective success.

“This is not a competition,” said Catmull. “If that group or that director is successful, then this is going to help everybody else in the company.”

The group’s fourth and final principle is to keep the attention on the problem, encouraging meeting participants to engage in engineering solutions. “Every once in awhile magic happens,” said Catmull. “You feel ego disappear from the room, all attention is on the problem,” he said. “Ideas come and go without people becoming attached to them. This is the state we aspire to.”

The five time Academy Award winner and author of Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration, also took time to discuss the role of failure in the creative process.

Catmull said that there are two kinds of failure: professional failure that one learns from and another kind ingrained in the education system where failing a test means to not measure up.

“Projects fail, companies fail, relationships fail,” Catmull said. “In politics and business, failures are used as bludgeons to attack opponents,” he said. “There is a palpable aura of danger around failure.”

Creators should try to separate the two meanings and understand that failure is “not a necessary evil,” but a “necessary consequence of doing something new,” he said.