30Mar2017

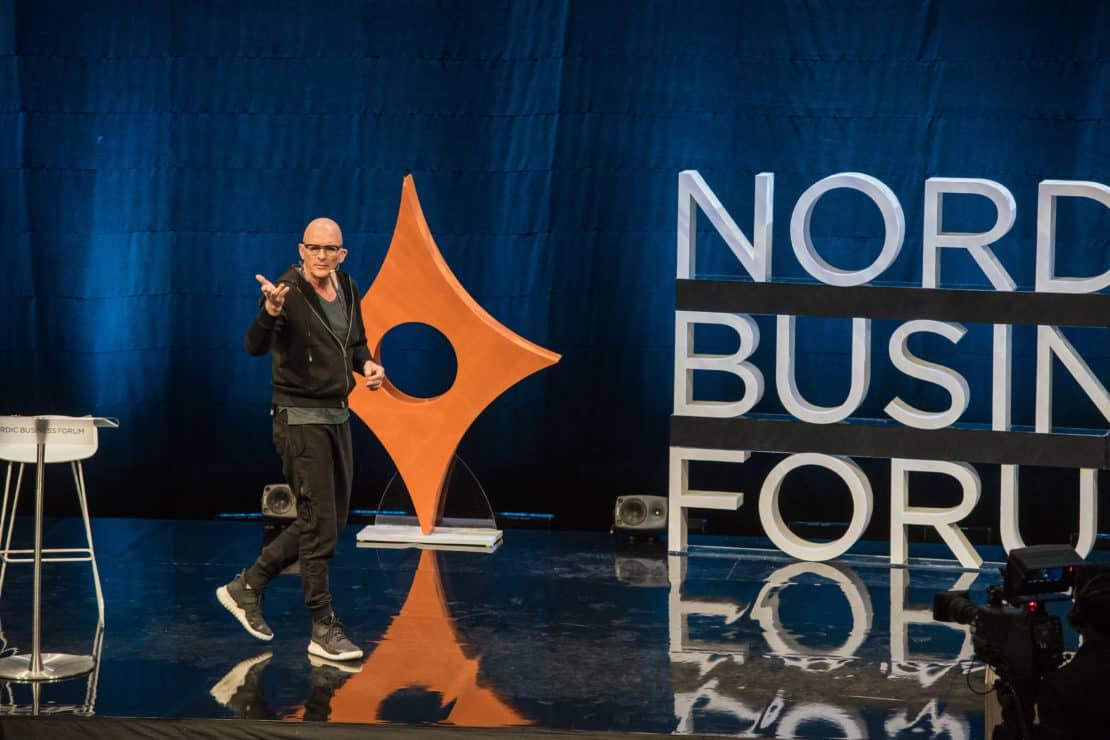

Kjell A. Nordström stands in front of a hometown crowd in Stockholm and proclaims that the Nordic region is “ultramodern”. What he means is that they tend to do things slightly before anyone else does them. And he just might be onto something, judging by the examples he gives.

The region itself is ultramodern in part because it is essentially a cooperative multinational metropolis of cities from 5 countries, which makes up 26 million people, and it’s the 9th largest economy in the world.

It’s the region that came up with the Trip Trapp—the embodiment of a somewhat radical idea that infants and toddlers should sit at the same level as parents at the dinner table. “How very Scandinavian,” Nordström dryly jokes. The seat adjusts with the child as he or she ages, making it the only seat they’ll need until adulthood. Again, quite ultramodern.

Nordström also cites the Volvo 242, possibly the greatest industrial success in Swedish history. The idea of building safety into heavy engineering for automobiles—again, very ultramodern. Without saying it in so many words, Nordström is hinting at the fact that this ultramodernity may just be where the world is headed. But one wonders as they hear this futuristic-looking man pace about the stage: what does this ultramodern world look like?

A Weird World

Nordström proclaims that the world is “kind of a weird, weird world“. It’s a world where, as Nordström notes, the incoming president of the United States is the former owner of Ms. Universe—a pageant of women marketed in the style of centerfolds. At the same time, companies who built their empires on centerfolds—Playboy, Hustler, and others—are all going bankrupt.

What is more ironic, Nordström notes, is that Playboy—the magazine most famous for centerfolds—doesn’t even have them in its pages anymore. The culprit, he notes, is technology.

To make his point, Nordström pulls a mobile phone from his pocket—but it’s hard to tell which one it is. That’s exactly the point. Nordström explains that the major players in mobile are producing phones that are basically indistinguishable from one another at 10 feet away. He refers to this as a “second order effect” of a chaotic system, which as he explains, is one we can’t see coming.

In the space of just 10 years, phones went from being so varied in their colors, shapes, and sizes, to being basically replicas of the same simple design: rectangles with a few buttons.

The same thing, Nordström continues, is happening with cars. They are all beginning to look the same. That’s because what is on the outside is not what people are concerned with—it’s just a shell for the important things, the customized things, inside. Within a decade or so, he explains:

“The car will be in the key…because the key will transform that piece of technology into a personalized piece of technology. And that’s your car, with your light, your Spotify lists…and when you turn the car off, it goes back to an anonymous piece of metal that looks almost the same as any other anonymous piece of metal.”

In essence, design in physical products is disappearing—being replaced, but by what? Nordström’s answer is what he calls “smart dust—computers that are so small that they are, in principle, dust.” The ramifications abound. You can have smart paint, smart cosmetics, and so on. Nothing is too small to be smart; an internet of things—increasingly small things.

Liquid fear, solid change

People’s feelings on this, Nordström notes, seem to be a bit mixed.

He invokes a notion coined by polish philosopher and sociologist Zygmunt Bauman: liquid fear. It’s a fear that we can’t put our finger on, but it’s a fear that something, somewhere is about to go wrong.

Nordström hypothesizes that this “liquid fear” was created by technology—much like the phenomenon of a Donald Trump presidency. Trump, Nordström proclaims “was created by technology…in the sense that he is the side effect of 35 years of intensive globalization that started in 1989.“

It’s a process that perhaps we weren’t quite ready for, because now, with an open world and immigration so widespread, some people are “pumping the emergency brake”.

And really, that’s not hard to imagine. After all, Nordström points out that what is happening around us now is 10 times faster than what we had experienced from the time of the industrial revolution until the 1980s. Not only that, but the technology we’re developing is about 300 times more powerful. Multiply those figures, and you get 3,000x—“and that’s the force that is hitting the political system,” Nordström proclaims.

“Something that is 3,000 times more powerful than when we were changing our society at a grand scale last time. So it should come as no surprise that some of us feel a little bit of liquid fear.” But Nordström brings some comfort to those who feel such liquid fear by assuring us that we “live in a matrix“—yes, just like the 1999 motion picture. What he means is that this 3,000x force of change that we’re living in can’t be derailed by Donald Trump, or any other world player, for that matter.

3K Power, 3 Points of Progress

In his analysis, there are 3 components to this new 3Kx Matrix world:

1. The world is now one capitalist system (with the exception of North Korea)

Nordström is quick to note that he’s not talking about capitalism as an ideology, but rather as a technology. “Think of it as a machine,” he says as he moves about the stage, “a machine that can only do one thing…it can sort things in to two piles…the efficient, the inefficient.” An interesting way to look at it, for sure.

“But the remarkable thing about this machine, is that you can feed anything into the machine.” He rattles off various commodities and services, and notes that thus far, all that we’ve done in our lifetime is to speed up the rate at which the machine sorts—which we’ve done with the help of technology.

2. The world is rapidly urbanizing

“We are in the beginning…of the fastest urbanization in human history,” Nordström tells the crowd. “We will now transform this planet from 200-ish countries to 600-ish cities.” He is quick to say that this will happen in our lifetimes—by about 2050, Nordström estimates. These 600 or so cities will then account for 80% of the world’s population, and between 90 and 95% of the world’s economic activity.

In nearly every developed country, the major city will be where 50% or more of the entire country’s population lives. Nordström notes that in Sweden, this is practically already the case—with the majority of people living in the greater Stockholm area. It’s also growing economically at a rate even faster than China—7 to 9% each year. That is at or above China’s universally lauded growth rate.

What is perhaps the most staggering aspect of this rapid urbanization is that at its peak, nearly all of us will be living on less than 1.5% of the world’s land mass. That’s pretty outrageous, when you think about it.

But what does a “city” mean in this sense? After all, if we’re basically all going to live in them—or at least depend on them for our economic well-being, it would help to understand what they are. Nordström explains that in essence, a city is simply a place where “a stranger can meet another stranger”. This is true because cities have always been places where people go, rather than where they are from. He cites Stockholm again as an example. 50% of the people there were not born there, and that figure continues to rise.

3. Anything that can be digitized will be

According to Nordström, we will need to keep our attention on what he abbreviates as “F.A.A.N.G”:

- Apple

- Amazon

- Netflix

These 5 companies now have such a firm grip on so many industries that they effectively set the standard for what comes next. Refer back to the efficient sorting machine that Nordström speaks about. This pile, 5-high, is the result of its operation. They continue to gain power because the most desirable new products are either digital, or directly involve digital stuff—yes, even cars—especially cars.

Monopoly money

The thing about this pile is that they are basically monopolies, and in being monopolies they have perfected the art of making money. For Nordström, that’s the only way to really make money in capitalism anyway—by being a monopoly.

Being a savvy guy, he is quick to assure the crowd at the Nordic Business Forum that he’s not talking about the strict legal definition of a monopoly. Rather, what he’s talking about is more of a “temporary monopoly,” as he puts it. It’s not a real monopoly; there are other options. But nearly all consumers feel tethered to what they’re currently using, and shudder to think of the effort and inconvenience involved in using a competing product.

The key to developing these temporary monopolies in the new Matrixified world, Nordström notes, is going to be innovation. Innovation is all about breaking out of the sameness in a given industry, and developing something that sets a new standard. When a company does that, they can tap into the power of the perceived monopoly. And of course, Nordström reminds us, that’s where the money is.

This article is a part of the Executive Summary of Nordic Business Forum SWEDEN. Get your digital copy of the summary from the link below.