16Jan2017

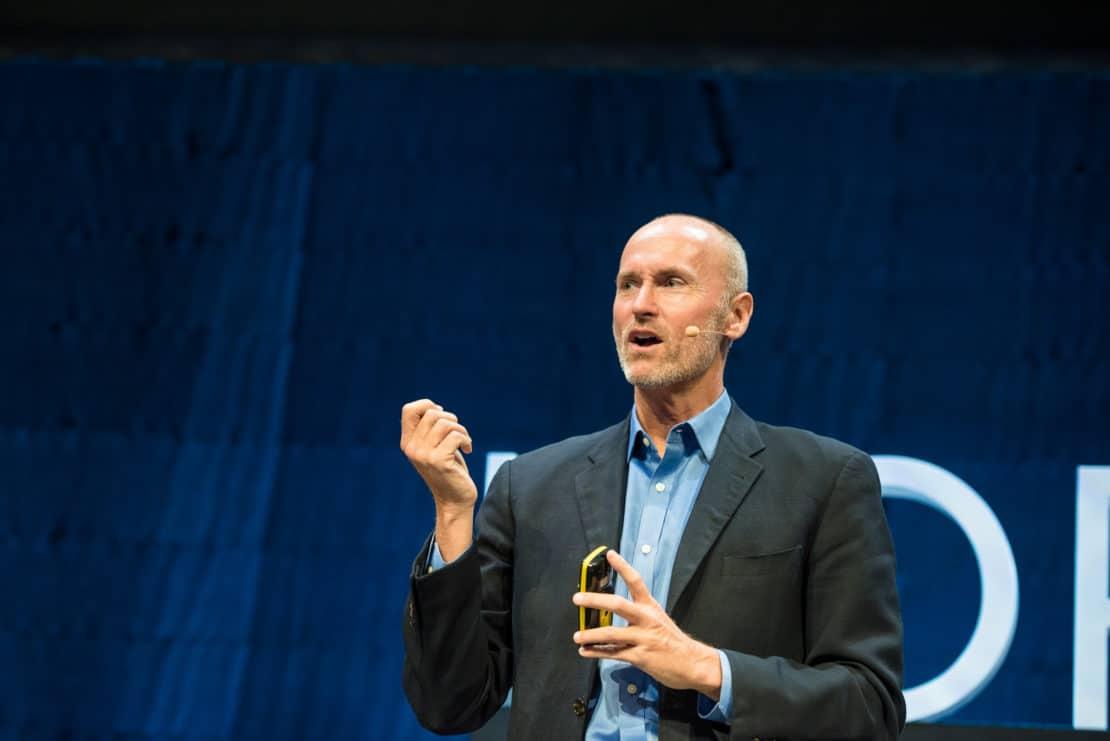

Engaging in and learning from feedback in an organization are probably the most difficult but potentially the most rewarding challenge any leader can set themselves. Easing the central tension between the giver and receiver of feedback can be a minefield of sensitivity, so anyone who gives some thought about how to understand and approach it is going to have an advantage.

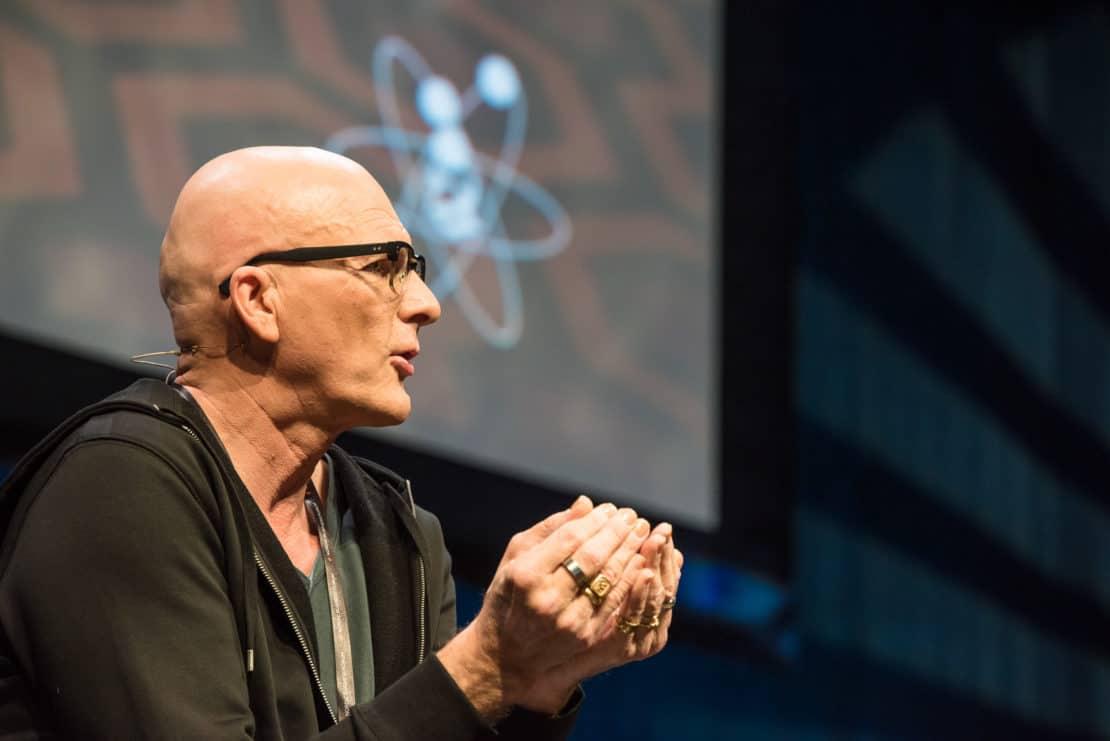

Most people don’t react well to critical feedback – unless they have been prepared to process it. Sheila Heen, founder of Triad Consulting Group, Lecturer in Law at Harvard Law School and involved in the Harvard Negotiation Project, has turned this kind of processing into something of an art form. Her books, Difficult Conversations and Thanks for the Feedback, tackle the skills of giving and receiving feedback as exactly that – skills that can be learned and improved.

“I have been going round the world helping leaders with their toughest conversations and we make a list on a flip chart and work on a list of things that concerned people in organizations,” she explains. “We started noticing a pattern. Feedback showed up 100% of the time. It didn’t matter why we were brought in to consult, or where it was in the world: we found that people all over the world are struggling with feedback conversations.”

She began to observe that there was plenty of learn about being an effective and skilled feedback giver, but the conversations were still hard. “Then it occurred to us that it’s the receiver who is in charge. They make the decisions to choose whether to act on the feedback or not. So we thought the real power is in understanding what is so hard about receiving feedback and that maybe it is a distinct leadership skill.”

Learning something new should be fun, so feedback should feel like a gift, says Heen. So why is it something we pass on to others and find hard to accept? “We want to be loved and respected the way we are now, that’s why. But the most important things come from your most painful experience.”

People react to feedback according to how and who gives it. “We think we would like to get the coaching from the people who are above us in an organisation, but in fact it can come most effectively from the people siting next to you. You’re not likely to take it so well from people you’re close to.” Feedback can be pretty loaded too. So you don’t like the pants your friend is wearing. Is it really the pants you don’t like, or something about the person?

Heen identifies three categories of feedback. The first is Appreciation, and she points out that 93% of workers in the United States feel unappreciated at work. The second is Coaching, the engine for learning, involving advice, suggestions, anything that is intended to support self-improvement. The third is Evaluation, the most familiar example of which might be school grades, and the category that produces the most reaction. “Part of the challenge is that we need all three, but when they get mixed up we lose the value of each.”